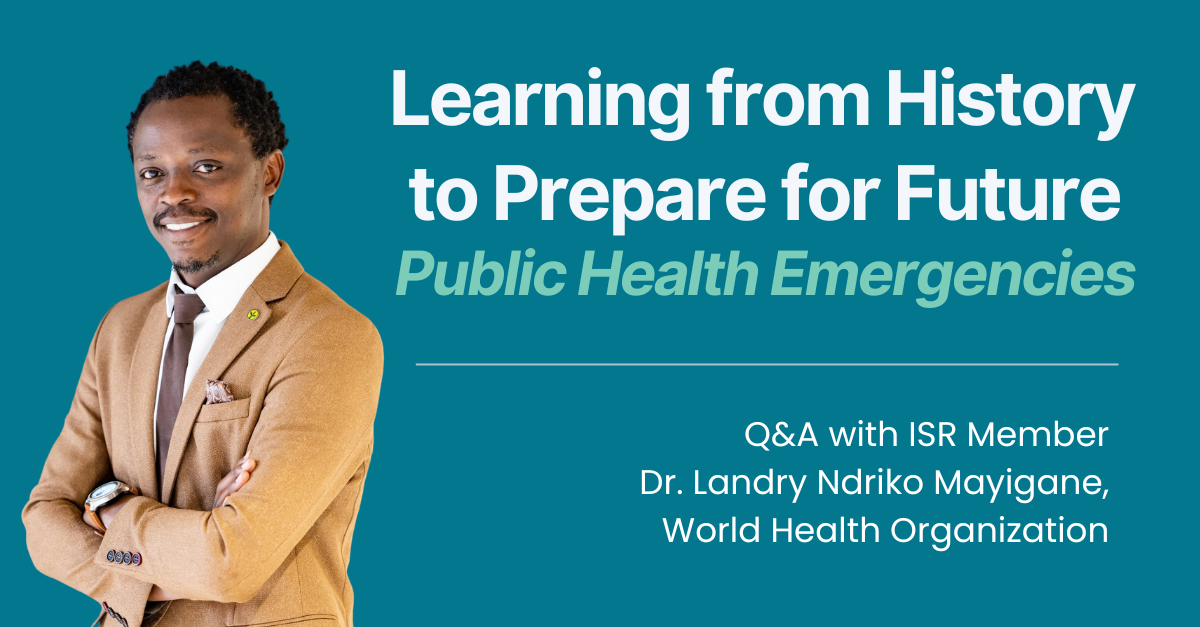

Learning from History to Prepare for Future Public Health Emergencies

by ISR Staff

Dr. Landry Ndriko Mayigane is a technical officer for health emergency preparedness and response at the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, Switzerland. In his role, he provides support to countries across the world to strengthen emergency preparedness and response capacities.

Dr. Mayigane recently spoke to the International Science Reserve about his work and how collaborations, like the ISR, can contribute to better responses to public health crises. The interview was undertaken in his personal capacity and not in his official WHO capacity.

How did you get involved in emergency preparedness and response?

I have over 20 years of experience working on health emergencies. My journey began by supporting Senegal in building its national emergency preparedness efforts for highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1). I went on to help West African countries respond to H5N1 when it was first declared on the continent in 2006, during my first UN assignment with the FAO’s Emergency Centre for Transboundary Animal Diseases.

In 2014, while working for the African Union, I led a complex response to the Ebola outbreak in Guinea. There, I supervised a team of over 120 multidisciplinary health workers from 11 countries. I was honored with a Medal of Service to Humanity by the AU Chairperson, H.E. Dr. Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, in recognition of my bravery and leadership demonstrated during the outbreak.

For nearly a decade, I have worked for WHO at both country and global levels. After Guinea, I moved to Mali to help the country build its capacity to prepare for and respond to health emergencies amid a compounded and protracted humanitarian crisis, particularly in the northern region.

During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in July 2020, after relocating from Mali to the World Health Organization (WHO) headquarters in Switzerland in 2018, I led the development of a performance assessment tool known as the Intra-Action Review (IAR). This tool has been used globally to support course correction, continuous learning, and the improvement of national and subnational response strategies for the pandemic and other protracted emergencies. An analysis conducted in 2022 showed significant benefits from its implementation. As of 2 April 2025, 193 IARs have been conducted by 92 countries and reported to WHO.

My current focus is on supporting countries in preventing, preparing for, and more effectively responding to future health emergencies—including the next pandemic—by building resilient learning systems.

You recently co-authored a piece about learning from public health emergencies through the crisis of knowledge failure. Why is learning from history important?

In public health, learning from history is crucial because it provides us with insights to guide future emergency responses. Past experiences reveal which strategies succeeded, highlight encountered challenges, and expose critical gaps in preparedness. By analyzing historical events, we can design resilient systems that are better equipped to handle emerging threats. We achieve this by leveraging the latest technology and developing systems that capture experiential knowledge from previous health emergencies. This approach creates a rich repository of lessons that bridges the gap between academic research and real-world practice.

However, common approaches to learning in this field have significant limitations. Traditional methods often rely on retrospective analyses and published studies, which can delay the integration of valuable insights into current policies. This lag hinders timely improvements in emergency response. Moreover, these approaches tend to overlook the nuanced, context-specific experiences of frontline responders, resulting in strategies that may be overly generic and less effective when applied to complex, dynamic situations. An overemphasis on quantitative data can also obscure the qualitative insights essential for understanding the full scope of challenges faced during crises.

Integrating historical lessons with experiential knowledge creates a more comprehensive learning process that fosters continuous improvement. This integration not only prevents the repetition of past mistakes but also promotes innovative, context-sensitive strategies for future outbreaks. Ultimately, embracing both quantitative analysis and qualitative wisdom strengthens public health systems, ensuring that our collective memory becomes a powerful tool in building a safer, more prepared global community.

Moreover, by actively incorporating lessons learned into dynamic training and simulation exercises, public health practitioners can rapidly adapt strategies as new challenges emerge. This proactive approach accelerates learning cycles and reinforces a culture of preparedness and innovation, ensuring that both policy and practice remain responsive to the ever-changing landscape of global health threats. Learning from history saves lives.

What is an Early Action Review (EAR)?

Early Action Reviews (EARs) are proactive tools in public health designed to detect and address emerging threats before they escalate into full-blown outbreaks. Rather than waiting for a crisis to develop, EARs promote a gradual learning process—emphasizing early detection, rapid notification, and swift response.

Central to this methodology is the use of the 7-1-7 target, a common benchmark that assesses the effectiveness of clinical, laboratory, and public health detection and response systems. Specifically, this target means that emerging threats should be detected within seven days, reported to the appropriate authorities within one day, and a comprehensive response initiated within seven days.

At the heart of the EAR approach is the integration of real-time data analysis with the practical insights of frontline responders and community stakeholders. This balanced method combines quantitative metrics—such as surveillance data and epidemiological trends—with qualitative observations from those directly involved in early response efforts. By merging these data sources, EARs offer a comprehensive picture of potential threats, facilitating a deeper understanding of both statistical trends and on-the-ground realities.

A key tactic within EARs is the implementation of scenario-based simulations and drills. These exercises test the robustness of existing emergency response plans under various hypothetical conditions, thereby revealing critical gaps and opportunities for improvement. Regularly conducting these reviews ensures that response strategies remain dynamic and adaptable, with resources optimally allocated before an outbreak intensifies.

Furthermore, EARs foster cross-sector collaboration by engaging experts from government, healthcare, and local communities. This collaborative framework builds a unified, flexible response system that is responsive to the complexities of real-world situations. Ultimately, EARs shift public health from a reactive, crisis-management stance to one of proactive preparedness and continuous learning.

By emphasizing early intervention, EARs not only help prevent local outbreaks from evolving into pandemics but also enhance the overall resilience of health systems, saving lives and equipping communities to face future public health challenges.

How can countries work together to prepare in advance for emergencies?

Public health emergencies, such as pandemics, do not respect national borders. To effectively respond, countries must proactively collaborate and develop synchronized preparedness plans. By employing standardized methodologies such as EARs, countries can effectively learn from each other regarding early detection, rapid notification, and swift response to public health emergencies. This shared approach enables countries to “speak the same language” through common tools and methodologies.

Importantly, such collaboration among countries is encouraged by the International Health Regulations (IHR 2005), an international legal framework designed to prevent and manage public health risks. For example, Caribbean countries recently integrated EARs into their emergency preparedness strategies with support from the Pandemic Fund. In November 2024, a multi-country EAR exercise was organized by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), in collaboration with the World Health Organization (Headquarters), the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA), and the 7-1-7 Alliance.

This event brought together participants from 12 Caribbean nations to enhance their capacities in outbreak detection, notification, and response. The participating countries included Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, British Virgin Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Each country contributed recent 7-1-7 target data from their most recent outbreak, and collectively, they explored strategies to integrate EARs into their national health systems. This exercise helped countries proactively identify shared threats, system failures, and good practices, harmonize response protocols, and build mutual trust.

With the support of PAHO and CARPHA, such EAR exercises support Caribbean countries in developing cohesive regional strategies. These strategies will ensure rapid, effective, and collective action to prevent and swiftly control public health crises as they emerge, ultimately safeguarding both local populations and the global community.

How does bringing together experts, such as public health researchers, other scientists, and emergency responders, help?

Such collaboration and partnerships, like with the ISR, facilitate the sharing of experiential knowledge, ensuring that insights gained from real-world emergencies inform science and predictive models, thus improving preparedness for and responses to future emergencies. By fostering continuous dialogue and joint action, these collaborations build trust and coherence among diverse stakeholders, enabling more effective and coordinated responses to health crises.

Moreover, integrating experiential knowledge and evidence-based science into decision-making processes enhances the adaptability and resilience of health systems, ultimately safeguarding communities worldwide. Everyone has a role to play in preventing the next pandemic.

Disclaimer: Institutional affiliation is provided for identification purpose only and does not constitute institutional endorsement. Any views and opinions expressed are personal and belong solely to the individual and do not represent any people, institutions or organizations that the individual may be associated with in a personal or professional capacity unless explicitly stated.