The Voices of the ISR

by ISR Staff

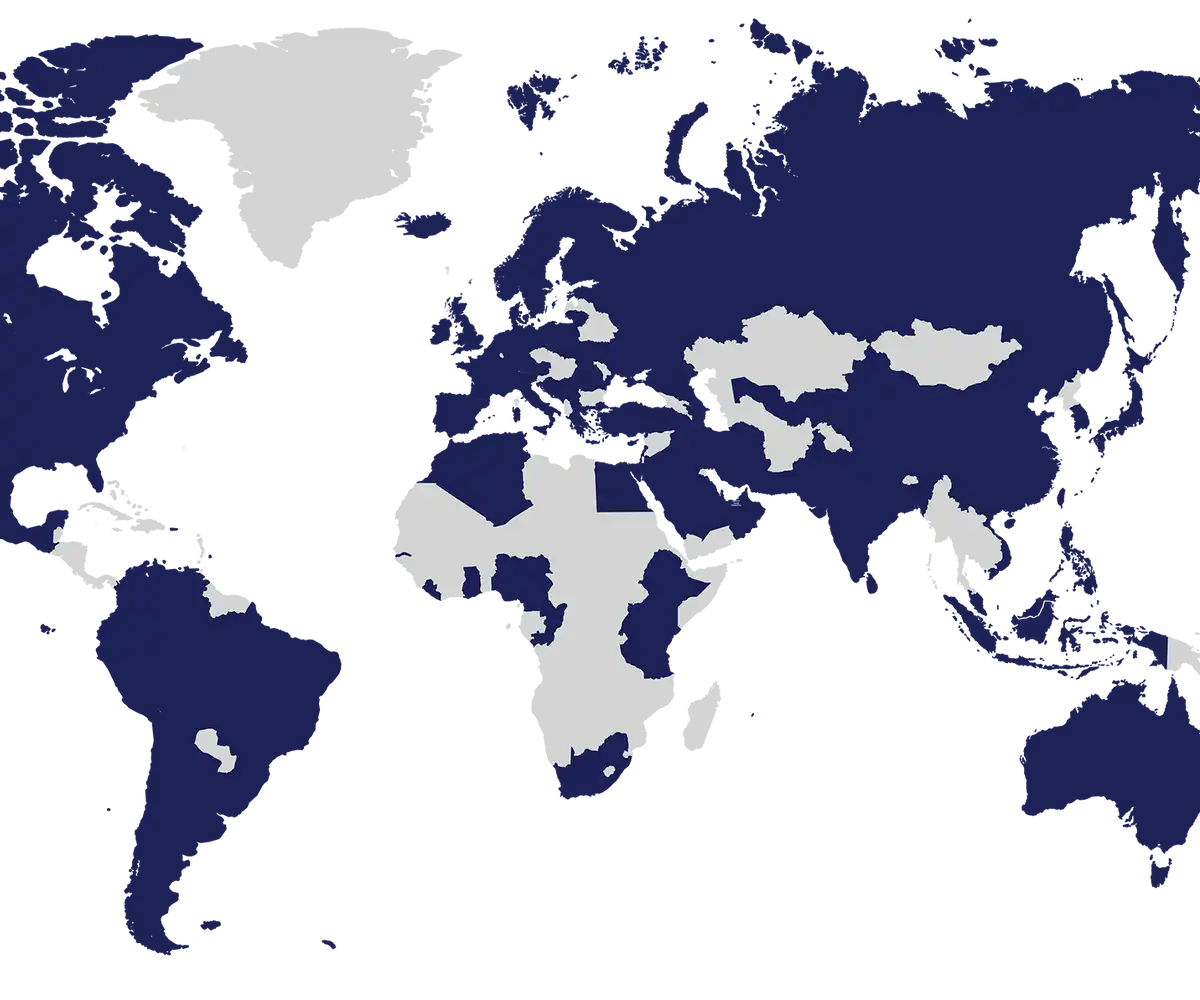

In March 2022, scientists from around the world participated in the ISR’s online simulation involving hypothetical wildfires in three countries. For this first Readiness Exercise, members of the ISR science community crafted research proposals responding to the three wildfire scenarios. The scientists who submitted proposals come from nine countries, including Brazil, Chile, Australia, the U.S., and the Philippines, and have varied research backgrounds, from paleoecology to behavioral science, from biology to mathematics.

We talked to these readiness pioneers about what motivated them to take part in the ISR exercise, and learn more about what they hold dear as scientists. They told us that the readiness exercise was an opportunity to think seriously about both a specific crisis scenario and scientific preparedness more broadly. They underscored the importance of cross-border collaboration and preparing well ahead of the next crisis.

Here are some highlights from these conversations.

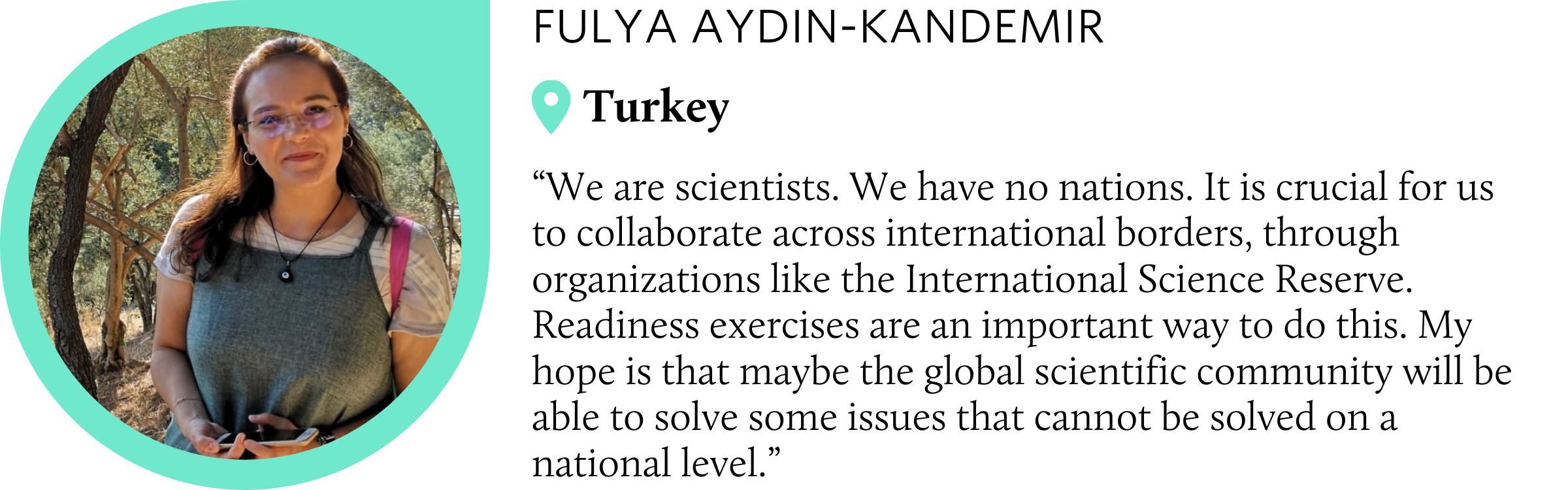

Fulya Aydin-Kandemir, Hydropolitics Association, Ankara & Akdeniz University, Antalya, Turkey

Fulya Aydin-Kandemir is based in Turkey and regularly collaborates with scientists internationally. She brings a scientific background in theoretical physics and life sciences to climate change research spanning geographic information systems, spatial analysis, remote sensing, climate change projections, and land use management. For her ISR readiness exercise proposal, Dr. Aydin-Kandemir (a graduate of Ege University Solar Energy Institute, Turkey) collaborated with colleagues from Turkey and Greece by drawing on several of these areas to elaborate a plan for GIS- and remote sensing-based mapping of regional water resources to assist both prevention and suppression of the ISR scenario’s Greek wildfire.

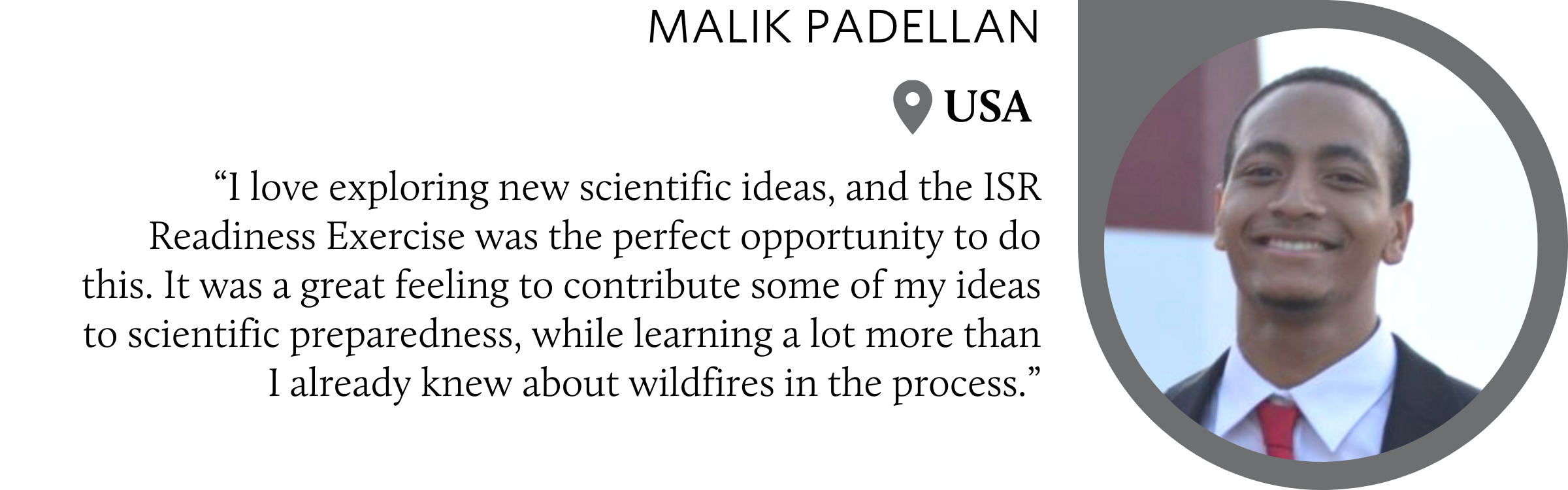

Malik Padellan, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Rensselaer, NY, United States of America

Malik Padellan is an early-career bioengineer who currently works as a process scientist, focusing on optimizing manufacturing processes. He has been involved with the New York Academy of Sciences since he was in school. For his readiness exercise proposal, Malik combined the ISR wildfire scenario with another scientific interest of his to propose testing wildfire spread detection through impact on modified fungal networks.

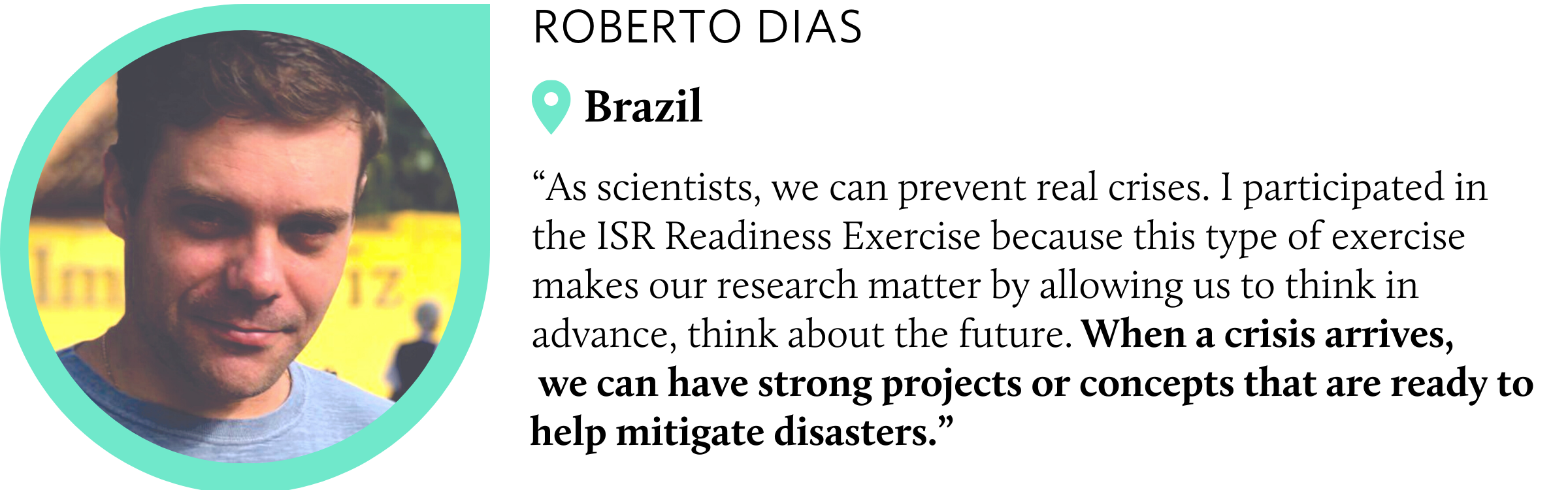

Roberto Dias, Scientific Director of Microbiotec, Fundação Arthur Bernardes/Petrobras, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Brazil

Roberto Dias is a biochemist in Brazil who directs research in molecular biology, virology and biotechnology. He currently focuses on using microbiological markers to aid the recovery of areas affected by climate change. Dr. Dias and his colleagues chose to address the ISR Northwestern US crown fire scenario for their ISR readiness exercise proposal. They considered how machine learning and predictive modeling could be used to understand the effect of wildfires on soil microbiota and support regional recovery.

Matthew Adeleye, The Australian National University, Australia

Matthew Adeleye is a paleoecologist who studies fossilized plant remains to understand long-term interactions—mainly Pleistocene and Holocene epoch—between ecosystems (vegetation and wetlands), fire, climate, and human impact. Although his current research in Nigeria and Australia focuses on terrestrial vegetation, Matthew has a longstanding interest in peatlands. This led him to address ISR’s Indonesian peat fire scenario for his readiness exercise proposal, which applied paleoecological insights and techniques to identify significant long-term impacts of the wildfire and fundamentally improve the region’s recovery.

Vinicius Albani, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil

Vinicius Albani is an assistant professor of mathematics who has a passion for combining theory and practical application. His recent international collaborations have included publications that have contributed to modeling the evolution of the covid-19 pandemic. In response to the ISR’s Northwestern US crown fire scenario, Dr. Albani and his colleagues proposed combining their expertise in mathematical, statistical and computational modeling with key wildfire data to form accurate long-term forecasts that could assist in both preparation and response.

Daniel San Martin, Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María, Chile

Daniel San Martin is a computer scientist who designs models to respond to and prevent Chilean wildfires. For his ISR readiness exercise proposal, Daniel chose to apply a Graphic Processing Unit (GPU) framework to ISR’s Greek wildfire scenario, using mathematical models and high-performance computing to implement real-time analysis and forecasting of fire dynamics that would allow faster and better decision-making in the response efforts, as well as prepare for future outbreaks.

Tracy Marshall, Department of Geography, The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago

Tracy Marshall studies households and their behaviors to assess, understand and improve their levels of disaster preparedness. She used this expertise and her professional background in risk, crisis and disaster management—including at the national level in Barbados—for her ISR readiness exercise proposal. Tracy proposed a socio-demographic, place-based household wildfire risk assessment that would save lives and make households more resilient, in response to the ISR’s Northwestern US crown fire scenario.

Daisy B. Badilla, Palawan, Philippines

Daisy B. Badilla is a chemical and environmental engineer who has studied biofiltration as an air pollution control technology. She briefly worked for the Philippine Nuclear Research Institute as Supervising Science Research Specialist and currently helps provide safe drinking water to indigenous communities in Palawan, Philippines. She is involved with the New York Academy of Sciences as a mentor in the Junior Academy and the 1000 Girls, 1000 Futures program. For her readiness exercise proposal, Dr. Badilla used her background in air quality research to explore minimizing the health impacts of the Indonesian peat fire scenario.

Avid Roman-Gonzalez, Business on Engineering and Technology S.A.C. (BE Tech), Universidad Nacional Tecnologica de Lima Sur (UNTELS) & Universidad de Ciencias y Humanidades (UCH), Peru

Avid Roman-Gonzalez is an electronic engineer specializing in areas including image processing, bioengineering and aerospace technology. His professional background includes work for companies such as the French Space Agency (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), as well as teaching appointments at multiple universities. For his ISR readiness exercise proposal, Dr. Roman-Gonzalez built on his existing work in risk and disaster management, and suggested using satellite images to improve localized wildfire response efforts.