Three experts’ takeaways on gearing up for the next global crisis

by Mila Rosenthal

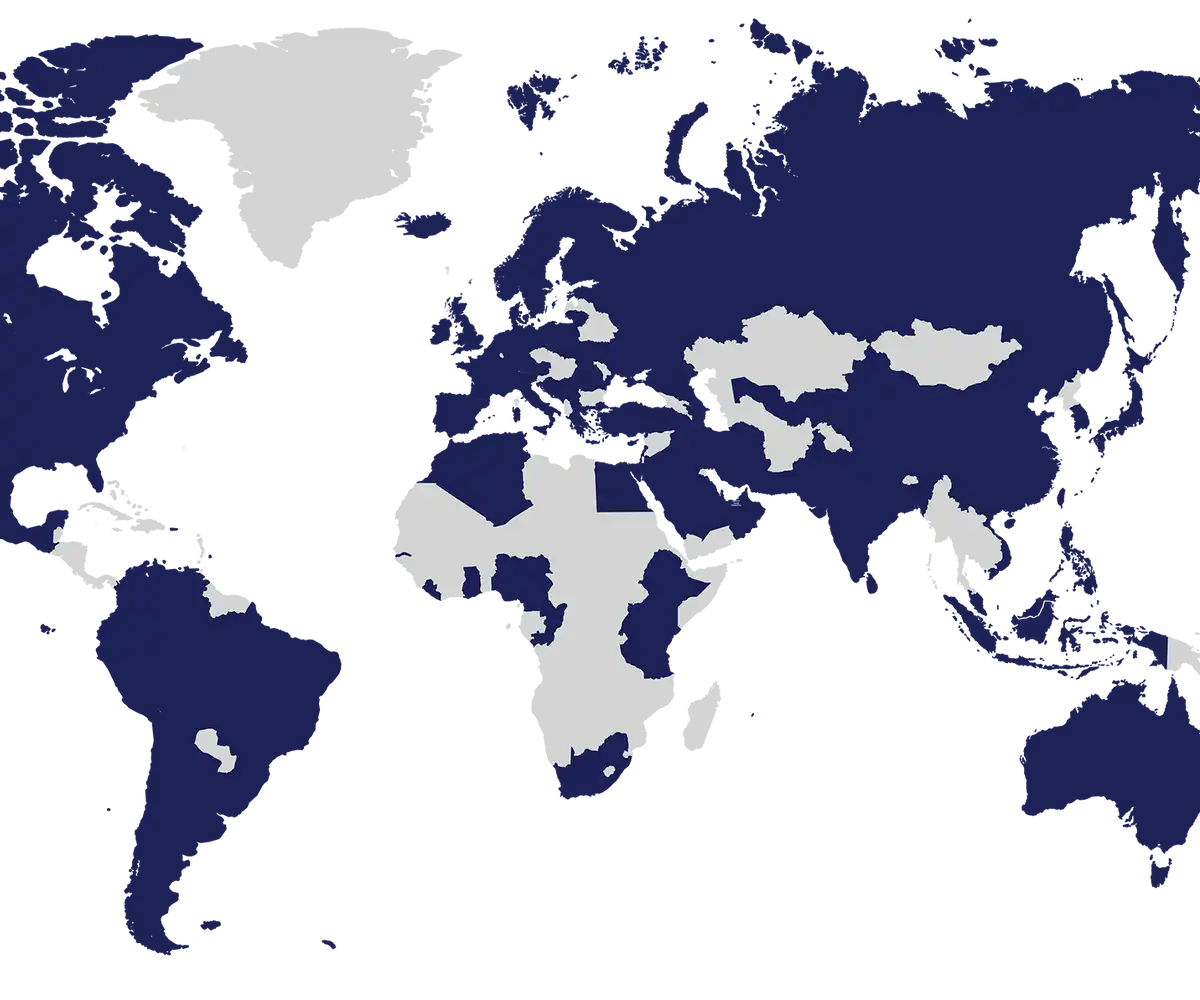

Since our launch in early 2022, the International Science Reserve (ISR) has rapidly expanded a network of scientists who are poised to respond to the next big crisis. The ISR aims to take action on crises that are complex, international, and where science and technology can effectively respond.

The ISR works in two ways, one through preparing for crisis by helping scientists in the community practice how they would respond during a crisis and understand what resources they need. And two, through a coordinated response to a declared crisis where the ISR will add to existing networks and support access to specialized human and technological resources.

With these goals in mind, the ISR brings together colleagues from a range of disciplines around the world for discussions to learn from each other in a semi-monthly webinar series: Science Unusual: R&D for Global Crisis Response.

The first webinar in this series was “Science Unusual: Gearing up for the Next Global Crisis.” The recording is now available on-demand through the New York Academy of Science. I was honored to moderate the discussion, and our esteemed panelists included:

- Dr. Fulya Aydin-Kandemir, Hydropolitics Association at Ankara & Akdeniz University (Turkey)

- Dr. Lorna Thorpe, Professor and Director of the Division of Epidemiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine in the Department of Population Health (United States of America)

- Alex Wakefield, Senior Policy Adviser, Royal Society (United Kingdom)

It’s hard to narrow down all the lessons I gleaned from this panel, but I have three big takeaways on what the panelists learned through their own experience preparing for and responding to crises in public health and climate change.

1) Scientists Need Stronger Networks to Connect and Coordinate Crisis Response

Alex Wakefield began her career in science policy to help governments use evidence and science to make stronger policy decisions. When the COVID-19 crisis hit in 2020, the UK government needed scientific evidence – but like many governments around the world – they didn’t have the luxury of time to do long-term research. Ms. Wakefield worked under the government’s chief scientist to run scientific advisory groups that convened experts to quickly provide evidence for policymaking decisions. That mechanism existed before COVID-19 to help deal with emergencies, like major flooding events and public health emergencies, and Ms. Wakefield believes it was a real advantage of the UK’s response that this was already in place.

Dr. Lorna Thorpe added that the energy of scientists wanting to get involved locally, nationally, and globally was one of the most important components of the COVID-19 response. She saw a robust convening and collaboration among institutions and researchers in New York City’s response, and she believes that the ISR can play a big role in facilitating these connections during the next major crisis.

2) Open Data Sharing is Essential to Effective Analysis During a Crisis

Dr. Fulya Aydin-Kandemir shared her own story of facilitating research during massive wildfires in Greece and Turkey in 2021. In her view, crisis research needs stronger access to public data, in her case satellite imagery, in order to respond faster and effectively to natural disasters across borders. That way, she could share her results with stakeholders, like firefighters, to help them understand real-time distribution of fires and how to stop outbreaks that can damage communities and ecosystems.

Dr. Thorpe added that we need more coordination of networks that allow research institutions to work together, no matter what their focus issues are, on issues like data sharing. Access to data like satellite imagery is not only important to issues of wildfires caused by climate change, but can also be important for real-time public health issues, like the urban heat effect or migration patterns.

3) To Build Public Trust, Leadership and Communication is Key

Research shows that the public will generally trust the government to do the right thing in a crisis. However, if there is ambiguity in leadership, Dr. Thorpe shared that she has seen the public lose trust – which makes it harder for technical leaders, like public health researchers, to do their job.

Dr. Thorpe reinforced how important great leadership is in a time of crisis, especially among local officials like mayors or health officials. During COVID-19, there was ambiguity around data that mired the United States and caused delays. She believes that some of that can be attributed to the erosion of institutions in America, but it is really about trusting your local leaders to make the right choices.

Ms. Wakefield believes that another way to build public trust ahead of an emergency is to consult with the public about what types of crisis responses are acceptable. Now at the Royal Society in the UK, she recently held a public dialogue series on different emergencies, like flooding and pandemics. The researchers found that the public had an expectation around government use of data – and they expressed concerns about when the emergency ends, what the data will be used for. The researchers plan to take these results and advocate for setting up stronger processes and policies for future responses.

Do you want to watch the whole webinar? Here are three steps to rewatch Science Unusual on-demand:

- Register for the webinar using this link

- Then, click “Join Event”

- After logging in, select the “Schedule” menu, or the grid menu (small squares) on mobile, located at the top of your screen, then click “On Demand”