Isolationism will make science less effective

by Mila Rosenthal

Increasing global scientific cooperation is fundamental to the mission of the International Science Reserve. Effective collaboration will positively impact how we solve global challenges.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a global human disaster. But the damage done could have been even worse had the spread of the virus not been countered by vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics, all developed by the medical and bioscience community at breakneck speed. In that success story, the people involved in the response tend to highlight one vital but often publicly overlooked ingredient: global scientific cooperation.

Could we achieve that level of international collaboration again? There are plenty of reasons to worry that we couldn’t.

First, over the past few years, we have witnessed intensifying economic and political competition between the United States and an increasingly assertive China. This rivalry is being played not just in tariffs, but in increased security restrictions on commercial technology exchanges and scientific collaboration.

An article by Keisuke Okamura last year in Quantitative Science Studies, the official journal of the international association of researchers who study the metrics of science, analyzed the impact of these tensions on scientific collaboration. Using data from published papers, Okamura found that the United States and China, after rapidly moving closer together for decades, had been moving apart since 2019.

Adding to this seismic shift in global relationships will be the potential impact of the new administration and its “America First” protectionist approach to supply chains, international climate standards, and public health cooperation. This potentially threatens our collective ability to respond to new and unexpected crises, as well as those we know too well. A recent Rand Corporation assessment of Global Catastrophic Risk found higher risk levels for hazards from sudden and severe changes to Earth’s climate, nuclear war, artificial intelligence, and pandemics from natural occurrence or synthetic biology.

International Scientific Collaboration Trending Up

Whether it is climate change, the need to build ethical standards for AI, geoengineering, or gene editing— all are science-based challenges that can only be addressed by global level collaboration. Encouragingly, the Okamura paper shows that the overwhelming trend towards international scientific cooperation over the past 50 years has been positive, with scientists from many institutions and countries in multiple scientific disciplines routinely working together.

It is crucial to the future of science that we develop new ways of being proactive, operating cohesively to promote solutions, safety, and stability across borders even as official relationships between states become more difficult. At the International Science Reserve (ISR) at The New York Academy of Sciences (the Academy), we have been promoting pathways for scientific cooperation, building a community that I believe can help function as a communal safeguard in the face of the threat posed by the scientific isolationist model.

Tens of thousands of scientists from more than 100 countries have signed up to the ISR network to be ready to work together in response to future cross-border crises. We help train and prepare scientists and experts on how to handle disasters, crises, and instability—and how to identify and get access to additional resources when needed.

Doomsday Scenarios

Since it is our job to think about doomsday scenarios, let’s talk through one.

Another pandemic hits. Politics— whether institutional or governmental have blocked researchers and medical professionals from different countries from talking, collaborating, and sharing data. Such lack of collaboration results in it becoming harder for us to understand why some regions of the world are being hit harder than others, because we lack the data to understand why. Meanwhile, scientists in other regions have the answer, but they are not sharing it. Lives are lost, economies wrecked, and we are all less safe. This is obviously a scary scenario.

The ISR was developed with the express goal of circumventing the barriers to collaboration. We help researchers talk to each other to build trust and share ideas through our digital hub. We develop games and scenarios to help them better prepare for decision-making in their own contexts when crises hit.

Customized Digital Games

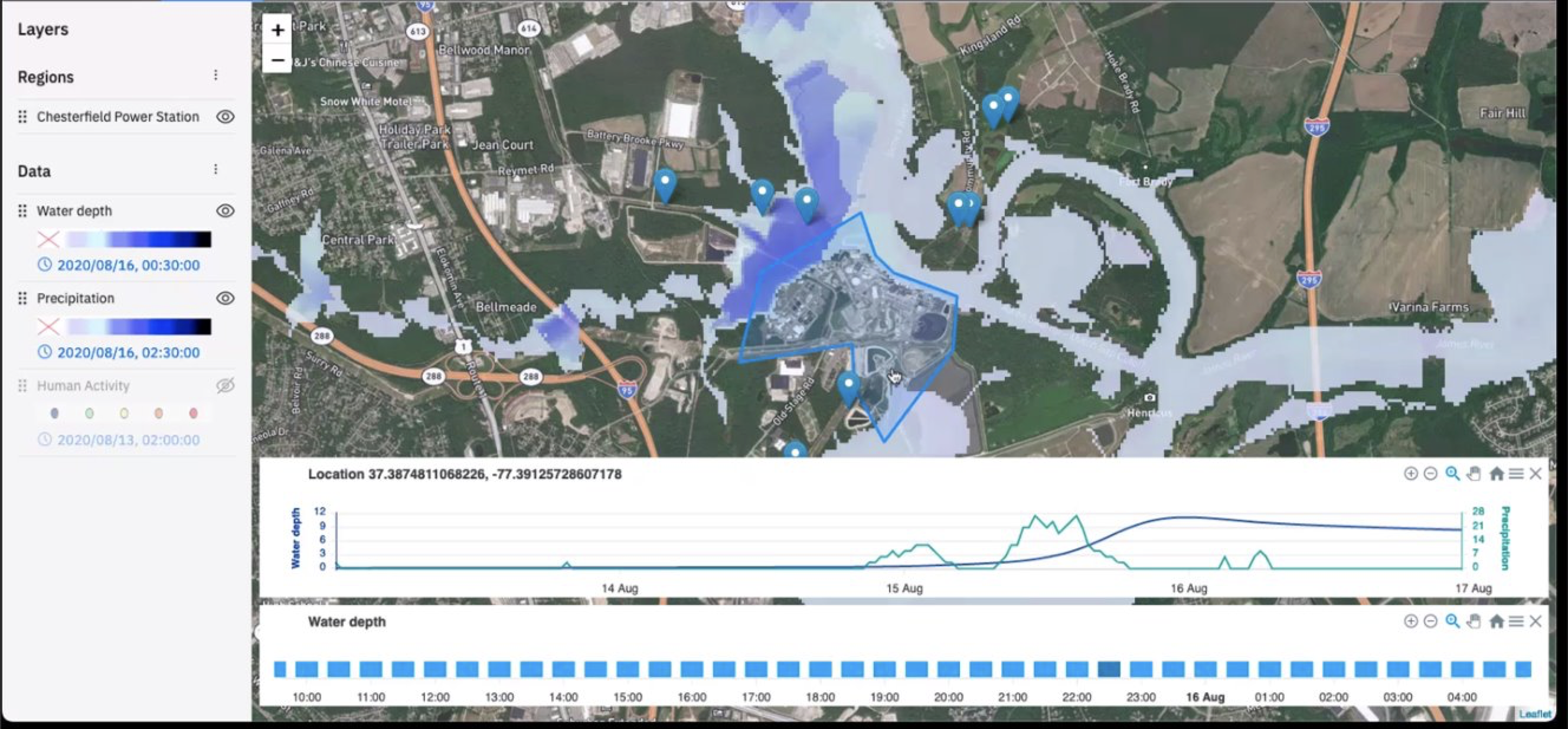

This year, for example, we partnered with the Center for Advanced Preparedness and Threat Response Simulation (CAPTRS) to build customized digital games to test how policymakers make decisions based on evolving scientific information during a crisis. We run scenarios on different kinds of crises—from extreme heat, mega wildfires, and floods to crop failures and new pathogen outbreaks—and we have explored and increased access to the data modelling and analysis tools that researchers need to respond to those. We also celebrate the work of ISR network members and uplift the stories of those who understand firsthand science’s role in global crisis response and help the public to better understand why this matters.

In our hypothetical scenario, the ISR is one of the spaces where scientists are communicating, generating support for each other, and sharing insights. They then can take that research and information back to their local contexts to strengthen their response. Of course, this scenario is hypothetical and high-level and perhaps idealistic. But at this moment, we need a clear vision to work together across borders to reduce harm and save lives.

We can’t predict what will happen next. Science can’t tell us what the day-to-day decisions of world leaders will be. But what we do know is global problems can only be effectively solved through sustained scientific collaboration. To achieve that we need to turn outward, not just inward.

Mila Rosenthal, PhD is the Executive Director of the International Science Reserve